A few weeks ago, I shared my personal history with college for all in my last post here. I believe, the primary appeal of the “college for all” model lies in its historical success for the elite and the lack of clear, alternative pathways to economic mobility for young people. However, I now believe this approach has significant drawbacks, which if unaddressed, are causing unnecessary harm. Today, I lay out my best understanding of why.

TL;DR

Here are the reasons why college for all is broken.

“College for all” is far from ALL.

College completion rates are dismal for students who grow up in low-income households

Cost has skyrocketed, leading to diminishing ROI

Underemployment of too many college graduates

Too many (about ⅓) college programs have a negative ROI

Many students today are interested in quality alternatives to college

I learn best by reading the arguments of and talking to smart people, especially those with whom I disagree. The best arguments I’ve heard to support college for all are:

Wage premium happens later in career

The alternatives might be worse

It’s what many parents want

Moving away from College for All will lead to lowered expectations

This conversation isn’t happening at elite boarding schools

In my next post, I will describe what I think those of us who work in education and/or influence policy and funding should consider doing.

1) Current state: What exactly happens with college-for-all?

My back of the napkin calculation is that roughly ⅓ of students from the BEST-performing charter school networks will ultimately earn a bachelor's degree.

I have the privilege of working closely with some of the best, most effective education leaders today. Some of the groups have or have had college-for-all missions (think KIPP, DSST, Uncommon, etc). In systems like these, roughly:

So, while it is impressive that the best networks can outperform the national average for all students, and significantly outperform the national average for low-income students, in my opinion their college completion rates are still unacceptably low to justify that as the sole postsecondary strategy.

2) Dismal completion rates

The 6-year completion rates (as illustrated above) for students who receive a Pell grant (proxy for low-income) are 49.2%. For students who go to a 2-year institution, that number drops to 33%.

The college for all model, when executed well, can close college access gaps. All things being equal, I think it is probably a good thing for students from low-income families to know that there is a college program available to them (far better to know that there is a quality college program available). However, significant equity gaps remain across race, income, and family’s education. Disturbingly, only 20% of first-gen college goers will end up with a bachelor’s degree.

Nationwide, over the past 50 years, degree attainment for students from the lowest income quartile has only increased from 6% to 11%.

3) Exploding costs, diminishing returns

Love it or hate it, the Biden administration’s attempts to forgive student loans has been a trillion dollar advertising campaign that the ROI on college is not what we hoped it would be. This is especially true for students who received a Pell grant.

According to research from the excellent Georgetown Center for Education and Workforce:

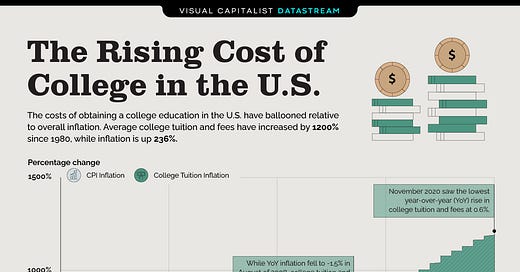

Tuition and fees at public four-year colleges have grown 19 times faster than the median family income since 1980, as funding for college has waned at both the state and federal levels, shifting much of the financial burden to students.

This point is illustrated nicely in the graph below:

4) Underemployment of college grads

More than half (52%) of recent four-year college graduates are underemployed (i.e. in a job that didn’t require a bachelor’s degree) a year after they graduate, according to a new report from Strada Institute for the Future of Work and the Burning Glass Institute. A decade after graduation, 45 percent of them still don’t hold a job that requires a four-year degree.

The Charter School Growth Fund (CSGF) recently did an excellent study of recent alumni. They similarly found that 42% of recent college graduates were underemployed (defined as in an early career that didn’t require a bachelor’s degree), and that 25% of BA holders were making less than the average earnings of HS graduates with no college experience.

5) Negative ROI for too many college programs

The CSGF findings are supported by data across the country. According to the Georgetown Center for Education and Workforce, 30% of college programs have a negative return on investment.

At 1,233 postsecondary institutions (30 percent of total), more than half of their students 6 years after enrollment are earning less than a high school graduate.

Even for students who make it through and complete college, in too many instances it is not a guarantee that they will be better off.

The Strada Foundation found that a similar percentage of recent college graduates question the value of their degree.

A meaningful share of bachelor’s degree holders do not feel their education was worth the cost — and outcomes differ by race and gender. About 1 in 3 recent bachelor’s degree graduates do not feel their education was worth the cost. A similar share earns less than $50,000 per year. Black alumni are least likely to experience these post-completion benefits, and women with bachelor’s degrees are less likely to earn a family-sustaining wage compared to men.

6) Listen to students

Ask any high school counselor these days. More and more students are questioning the idea that college is a golden ticket. Even at college-preparatory schools, where there is a heavy emphasis on building a “college-going identity” not all students want to go to college nor choose to enroll after graduating high-school.

Gallup which has the best longitudinal data about perceptions of higher education reported last year:

“Americans’ confidence in higher education has fallen to 36%, sharply lower than in prior readings in 2013 (70%), 2015 (57%), and 2018 (48%). With the starkest decline in young adults (ages 18-29).”

Best arguments for a “College for All” approach.

1) Wage premium happens later in career

David Demming who does fantastic work at Harvard and at the Harvard Workforce Project, argued last fall in the Atlantic that the college backlash has gone too far.

The diminishing college wealth premium “ however, suffers from a key oversight. In estimating the lifetime earnings for people who are now in their 30s and early 40s, the researchers assumed that the college wage premium will stay constant throughout their life. In fact, it almost surely will not. For Baby Boomers, Gen Xers, and older Millennials, the college wage premium has more than doubled between the ages of 25 and 50, from less than 40 percent to nearly 80 percent. Likewise, the college wealth premium for past generations was initially very small but grew rapidly after age 40. History tells us that the best is yet to come for today’s recent graduates.”

Demming’s argument may be correct (the data don’t exist to prove it). However, he makes the same fallacy that most researchers make looking at the impact of college. They rarely establish a causal relationship, comparing similar graduates to non-graduates, rather they compare averages. In a world where richer students are far more likely to both go, and complete college, it shouldn’t surprise us that they remain (and become) richer, than the poorer students who are less likely to go and complete.

2) The alternatives might be worse

While we now have a better understanding of outcomes for students who attempt college, we don’t understand the outcomes for students who attempt alternatives. This is a fair and important critique and it’s an imperative to support research and policy to understand what programs are working, why, and which aren’t. There are some specific programs that have been studied and shown concrete positive value. For example:

Per Scholas, an IT short-term training program (and ActivateWork program partner) has shown to increase participants' wages years after the program, and reduce dependence on SNAP.

CrossPurpose, a workforce nonprofit, participated in a study that showed for every dollar invested in the program, it generated a $6.45 return in increased earnings, taxes, and reduction in public spending.

Where we do have data on short-term training and certificates is from accredited providers. Michael Itkowitz then at Third Way, showed that just over half pay off within 10 years, and 42% will never show a positive ROI.

More study is needed here. I’m grateful to the work that Julie Stone, Roger Lowe, and others in Colorado are doing on this. If short-term PELL ever happens (which I believe it should), keeping an outcomes and accountability orientation is key.

3) It’s what many parents, and more Black, Asian, and Hispanic parents, want

I’m a big believer in school choice and a diversity of school models, so why shouldn’t we have college preparatory schools for the parents who want that?

4) Bigotry of low expectations

This is the biggest hangup for most of my colleagues that run great college-prep charter school networks. They desperately (and rightly) want to avoid going back to an inequitable world of tracking. This is an important instinct, and one that is substituting “college” for academic rigor and/or high expectations for all students.

5) This conversation is not happening at elite private schools

I think this is largely true (although shifting somewhat). And for most students at elite private schools, college has worked better, and it’s a lower consequence outcome for a rich kid when it doesn’t work. Wishing the world worked better, isn’t as productive as preparing students for the world as it is.

Concluding thoughts

For a deeper dive in the data, the best report I’ve read, learned from, and borrowed a bit from here is Alex Cortez’s report from Bellwether last year, An Investment, not a Gamble. He writes:

Completing a postsecondary education pathway like a two- or four-year college degree is widely considered a pillar of the American dream. But for too many Americans, particularly those from systemically marginalized communities, the postsecondary system isn’t the sound investment in their future it’s marketed to be. Instead, it’s a high-stakes gamble.

What am I missing, what do you disagree with? I’m writing here to try to sharpen my thinking, and am appreciative of the many people who have shared their thinking, ideas and research with me.

Polls

Last month’s poll

In my next post, I will lay out what I think we (equity-minded practitioners, funders, and policymakers) should do to best support young people, especially those from historically marginalized communities, in realizing their full potential and maximizing economic and social mobility.

Onward,

James

Great great post bringing it all together in one place

This is an all-time great essay. CGSF should distribute it.